For many people, male and female refer to natural categories that neatly divide up the human population. Often, people associate these two categories with different abilities and personality traits. Setting aside these ideas and assumptions, anthropologists explore aspects of human biology and culture to understand where notions of gender come from while documenting the diversity of gender and sexuality in cultures all over the world, past and present.

In the social sciences, the term sex refers to the biological categories of male and female (and potentially other categories, as discussed later in this chapter). The sex of a person is determined by an examination of biological and anatomical features, including (but not limited to): visible genitalia (e.g., penis, testes, vagina), internal sex organs (e.g., ovaries, uterus), secondary sex characteristics (e.g., breasts, facial hair), chromosomes (XX for females, XY for males, and other possibilities), reproductive capabilities (including menstruation), and the activities of growth hormones, particularly testosterone and estrogen. It may seem as though nature divides humans neatly into females and males, but such a long list of distinguishing factors results in a great deal of ambiguity and diversity within categories. For instance, hormonal influences can produce results different from the ways that people typically develop. Hormonal influences shape the development of sex organs over time and can stimulate the emergence of secondary sex characteristics associated with the other sex. Clothes on or clothes off, people can have body features associated with one sex category and chromosomes associated with another.

While sex is based on biology, the term gender was developed by social scientists to refer to cultural roles based on these biological categories. The cultural roles of gender assign certain behaviors, relationships, responsibilities, and rights differently to people of different genders. As elements of culture, gender categories are learned rather than inherited or inborn, making childhood an important time for gender enculturation. As opposed to the seeming universality of sex categories, the specific content of gender categories is highly variable across cultures and subject to change over time.

The two terms, biological sex and cultural gender, are often distinguished from one another to clarify the differences embedded in “nature” versus the differences constructed by “culture.” But are biological sex categories based on an objective appraisal of nature? Are sex categories universal and durable? Some scholars question the biological objectivity of sex and its opposition to the more flexible notion of gender.

Associated with sex and gender, the concept of sexuality refers to erotic thoughts, desires, and practices and the sociocultural identities associated with them. The complex ways in which people experience their own bodies and perceive their own gender contribute to the physical behaviors they engage in to achieve pleasure, intimacy, and/or reproduction. This complex of thoughts, desires, and behaviors constitutes a person’s sexuality.

Some cultures have very strict cultural norms regarding sexual practices, while others are more flexible. Some cultures confer a distinctive identity on people who practice a particular form of sexuality, while others allow a person to engage in an array of sexual practices without adopting a distinctive identity associated with those practices (Nanda 2000). Sexual orientation refers to sociocultural identities associated with specific forms of sexuality. For instance, in American culture, sex between a woman and a man is conventionalized into the normative identity of heterosexual. If you are a person who practices that kind of sex (and only that kind), then most Americans would consider you to be a heterosexual person. If you are a person who engages in sex with someone of the same sex/gender category, then in American culture, you would be considered a gay person (if you identify as male) or a lesbian (if you identify as female). So anxious are Americans about these categorical identities that many young people who have erotic dreams or passing erotic thoughts about a same-sex friend may worry that they are “really” not heterosexual. As American norms have changed over the past several decades, some people who have romantic, emotional, or erotic feelings toward people of their own gender and another gender have adopted the identity of bisexual. People who may have erotic desires about and relations with others without regard to their biological sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation may consider themselves to be pansexual. Even more recently, some people who do not engage in sexual thoughts, desires, or practices of any kind have embraced the identity of asexual. While there are many aspects and manifestations of sexual orientation, sexual orientation is considered to be a central and durable aspect of a person’s sociocultural identity.

In some cultures, heterosexuality was previously thought to be the most “natural” form of sexuality, a notion called heteronormativity. This notion has been challenged by research and the growth of the global LGBTQIA+ movement. In many other cultures, people are allowed or even expected to engage in more than one form of sexuality without necessarily adopting any specific sexual identity. This is not to say that these other cultures are consistently more liberal and tolerant of sexual diversity. In many societies, it is acceptable for people to engage in same-sex practices in certain contexts, but they are still expected to marry someone of the opposite sex and have children.

Scholars who have studied sexuality in many cultures have also pointed out that a person’s gender identity, sexual orientation, and sexuality tend to change significantly over the life span, responding to different contexts and relationships. The term queer, originally a pejorative term in American culture for a person who did not conform to the rigid norms of heterosexuality, has been appropriated by people who do not abide by those norms, particularly people who take a more situational and fluid approach to the expression of gender and sexuality. Rather than a set of fixed and durable identities, queer gender and sexuality are more fluid, constantly emerging, and contingent on multiple factors.

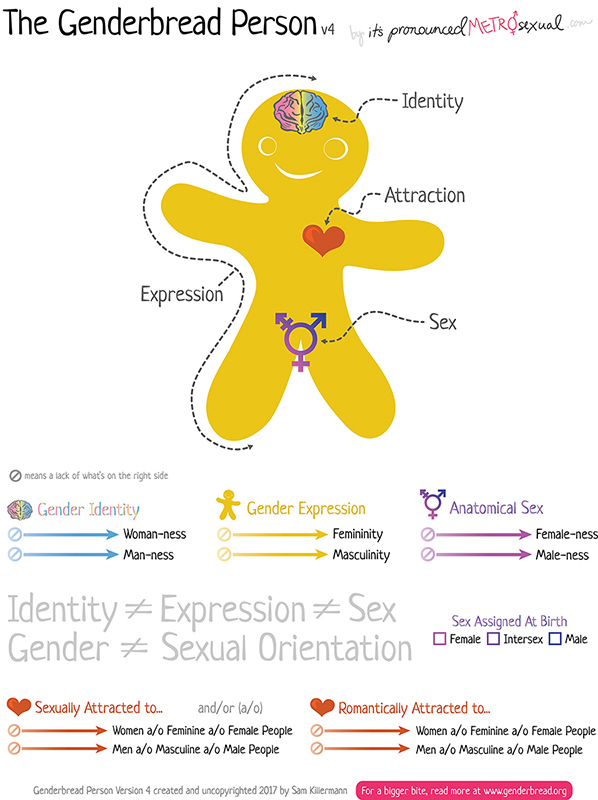

As complex as sex, gender, and sexuality can be, it is helpful to have a diagram illustrating the possible relationships among these factors. Activist Sam Killermann has developed a useful diagram known as “The Genderbread Person,” depicting the various aspects of identity, attraction, expression, and physical characteristics that combine in the gender/sexuality of whole persons.

Given humans’ close biological relationship to primates, one might expect to see similar dynamics of sex and gender between human and nonhuman primate social groups. Biologists and primatologists have examined sex differences in the biology and behavior of both nonhuman and human primates, looking for commonalities that might suggest a common biological genesis for sex/gender categories.

In the 1950s, a time when American men were supposed to be breadwinners and American women were urged to be housewives and mothers, most primatologists believed that males were the public actors in primate social life, while females were passive, marginal figures. Primatologists of the time believed that males constantly competed against one another for dominance in a rigid group hierarchy, while females were more narrowly interested in raising young (Fedigan and Fedigan 1989). In fact, primatologists described the total social organization of primates in terms of male competition. This view went along with Charles Darwin’s notion that males are forced to compete for the opportunity to mate with females and so, therefore, must be assertive and dominant. Females, in Darwin’s theory, were shaped by evolution to choose the strongest male to mate with and then concern themselves exclusively with nurturing their offspring to adulthood.

By the 1980s, however, a number of strong studies were showing some very surprising things about primate social organization. First, most primate groups are essentially composed of related females, with males as temporary members who often move between groups. The heart of primate society, then, is not a set of competitive males but a set of closely bonded mothers and their young. Females are not marginal figures but central actors in most social life. The glue that holds most primate groups together is not male competition but female kinship and solidarity.

Second, social organization in primates turned out to be incredibly complex, with both males and females actively strategizing for desirable resources, roles, and relationships. Research on a number of primate species has demonstrated that females are often sexually assertive and highly competitive. Female primates actively exercise their preference to mate with certain male “friends” rather than aggressive or dominant males. For males, friendliness with females may be a much better reproductive strategy than fighting with other males. Moreover, many primatologists have begun to identify cooperation rather than competition as the central feature of primate social life while still recognizing competition for resources by both males and females in their pursuit of survival and reproduction (Fedigan and Fedigan 1989).

What this means, in a nutshell, is that (1) both females and males are competitive, (2) both females and males are cooperative, and (3) both females and males are central actors in primate social life.

While evidence suggests that in primate groups males and females are equally important to social life, this still leaves open the question of biological differences and their link to behavioral differences. The anatomy of primate males and females differs in two main respects. First, of course, adult females can and often do experience pregnancy and bear offspring. The females of most primate species are often pregnant or nursing for most of their adult lives and devote more time and resources to care of young than males do (although there are some notable exceptions, such as certain species of New World monkeys). And some researchers have noted the tendency of juvenile females to pay more attention to primate babies in the group than do juvenile males.

Second, male primates tend to be slightly bigger than females, although this difference itself is quite variable. The size difference between males and females of any species is referred to as sexual dimorphism. Male and female gibbons are nearly the same size, while male gorillas are nearly twice the size of females. Female chimpanzees are about 75 percent the size of males. Human females are about 90 percent the size of males, making human sexual dimorphism closer to gibbons than chimpanzees.

Some researchers suggest that a high level of sexual dimorphism is associated with strong male dominance, rigid hierarchy, and male competition for mating with females. Certainly these features reinforce one another in gorilla society. A low level of sexual dimorphism may be associated with long-term monogamy, as with gibbons. However, anthropologist Adrienne Zihlman cautions against making any firm judgments about the relationship between biological features such as size and behavioral features such as sexual relations. She remarks, “There is no simple correlation between anatomy and behavioral expression, within or between species” (1997, 100). Reviewing research on sex differences in gibbons, chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans, she concludes that each species features a unique “mosaic” of sex differences involving anatomy and behavior, with no clear commonality that might predict what is “natural” for humans.

Humans’ closest primate relatives are chimpanzees and bonobos, both sharing 99 percent of their DNA with humans, and yet each species exhibits very different gender-related behaviors. Bonobos are female-dominant, while chimpanzees are male-dominant. Bonobo groups are mostly egalitarian and peaceful, while chimpanzee groups are intensely hierarchical, with frequent male aggression between groups. Sexual behavior among bonobos is remarkably frequent and extraordinarily variable, with a wide range of same-sex and opposite-sex pairings involving various forms of genital contact. Some researchers believe that sexual contact helps build social bonds and ease conflicts in bonobo groups. Bonobos have been called the “make love, not war” primate. Sexual behavior among chimpanzees is also variable but much more limited to opposite-sex pairings. A female in estrus may mate with several males, a pattern called opportunistic mating. Short-term exclusive relationships may form, in which a male guards a female to prevent other males from mating with her. Consortships also happen, in which a female and a male leave the group for a week or more.

With such variability between humanity’s two closest DNA relatives, it is impossible to use nonhuman primate behavior to make assumptions about what is “natural” for human males and females. In fact, with regard to gender, the lessons of primatology may be that apes (like humans) are biologically quite flexible and capable of many social expressions of gender and sexuality.

Just as with primate research, research on human biological sex/gender differences has been considerably slanted by the gender bias of the (often male) researchers. Within the Euro-American intellectual tradition, scholars in the past have argued that women’s biological constitution makes them unfit to vote, go to college, compete in the job market, or hold political office. More recently, beliefs about the different cognitive abilities of men and women have become widespread. Males are supposedly better at math and spatial relationships, while females are better at language skills. Hormonal activities supposedly make males more aggressive and females more emotional.

In her book Myths of Gender, biologist Anne Fausto-Sterling (1992) conducts a massive review of research on cognitive and behavioral sex/gender differences in humans. Looking very closely at the data, she finds that the vast number of studies show no statistically significant difference whatsoever between the cognitive abilities of boys and girls. A minority of studies found very small differences. For instance, among four studies of abstract reasoning abilities, one study indicated that females were superior in this skill, one study indicated that males were superior, and two studies showed no difference at all. Overall, when differences are found in verbal abilities, girls usually come out ahead, but the difference is so small as to be irrelevant to questions of education and employment. Likewise, more than half of all studies on spatial abilities find no difference between girls and boys. When differences are found, boys come out ahead, but the difference is again very small. Looking at the overall variation of skill levels in this area, only about 5 percent of it can be attributed to gender. This means that 95 percent of the differences are due to other factors, such as educational opportunities.

Even these tiny differences that may exist in the cognitive talents of different genders are not necessarily rooted in biological sex differences. Several studies of spatial abilities have shown that boys may initially perform better on spatial ability tests, but when given time to practice, girls increase their skill levels to become equal to boys, while boys remain the same. Some researchers reason that styles of play such as sports, often encouraged more by parents of boys, may build children’s spatial skills. Parenting styles, forms of play, and gender roles—all elements of culture—may shape the data more than biology. Cross-cultural studies also indicate that culture plays an important role in shaping abilities. A study of the Inuit found no differences at all in the spatial abilities of boys and girls, while in a study of the Temne of Sierra Leone, boys outperformed the girls. Inuit girls are generally allowed more freedom and autonomy, while Temne girls are more restricted in their activities.

Similar complexities emerge in the analysis of studies on aggression. Fausto-Sterling found that most studies revealed no clear relationship between testosterone levels and levels of aggression in males. Moreover, testosterone aggression studies have been riddled with problems such as poor methodology, questionable definitions of aggression, and an inability to prove whether testosterone provokes aggression or the other way around. Where differences in aggression between girls and boys are documented, some researchers have concluded that cultural factors may play a strong role in producing those differences. Anthropologist Carol Ember studied levels of aggression among boys and girls in a village in Kenya. Overall, the boys exhibited more aggressive behavior, but there were exceptions. In families lacking girl children, boys were made to perform more “feminine” work such as childcare, housework, and fetching water. Boys who regularly performed those tasks exhibited less aggression than other boys—up to 60 percent less for boys who performed a lot of this work.

As with the primate research on sex differences, research on the brains, bodies, and behaviors of male and female humans does not seem to suggest that significant behavioral differences are biologically hardwired. While researchers have discovered differences in the cognitive talents and social behaviors of males and females, those differences are very small and could very well be due to social and cultural factors rather than biology. As with bonobos and chimpanzees, humans are biologically quite flexible, allowing for a diverse array of forms of gender and sexuality.

Seeking to understand the origins of human sociocultural formations of gender and sexuality, some researchers have turned to the archaeological record. Archaeologists use temporal sequencing, fossil evidence, comparison with living communities, and knowledge of the evolutionary process to piece together an understanding of the development of gendered and sexual behaviors in the context of human evolution.

Early theories of gender in human evolutionary history were shaped by the “man the hunter” hypothesis. In the 1950s and ’60s, many anthropologists believed that hunting constituted the primary means of subsistence throughout humans’ evolutionary past, up until the domestication of plants and animals around 10,000 years ago. As hunting was mainly done by men in contemporary gathering-hunting societies, researchers assumed that hunting was naturally and exclusively a male activity throughout prehistory. Women could not hunt, it was thought, due to the burdens of pregnancy, nursing, and childcare. It seemed likely that adult women stayed together with their children at the home base while men went out in small groups in search of game. In this view, tools were invented for hunting and processing meat and were mostly made by men. Dependence on meat gave men power and prestige, leading to male dominance over females. Hunting also spurred the development of language because communication was necessary to coordinate hunting expeditions. Tools and language, in turn, stimulated the development of larger brains. Hunting by men was therefore thought to be the central driving force in the evolution of humans’ hominid ancestors.

In the 1970s, researchers from the emerging field of sociobiology drew from the “man the hunter” hypothesis to claim that certain gender roles and sexual relations evolved to be natural among humans. Sociobiology is a subfield of biology that attempts to explain human behavior by considering evolutionary processes. In regard to gender roles, for instance, sociobiologists sought to understand how evolution may have shaped men and women differently, encouraging gender-specific strategies for survival and reproduction. Many sociobiologists have argued that men, as hunters, evolved to be strong and aggressive, able to strategize in groups but in fierce competition to achieve the status of dominant male; in contrast, women were primarily engaged in childcare and food preparation and therefore evolved to be more nurturing and submissive, focused on attracting the attentions of men. Dependent on men to supply meat for themselves and their children, women would have been motivated to ensnare men in long-term monogamous relationships to ensure a constant food supply as well as protection from other aggressive males. Largely free from the responsibilities of childcare, men would have been motivated to mate with as many females as possible to ensure the greatest number of descendants. This view of the natural order of gender relations became very popular and widespread in American society.

Less well-known in American society is the thorough critique of the “man the hunter” hypothesis within archaeology and throughout the other subfields of anthropology. Around the same time that sociobiologists were elaborating on their theories of gender, many anthropologists were pushing back against the notion that hunting was the primary subsistence activity of gathering-hunting societies. As you’ll recall from the discussion of such societies in, Work, Life, and Value: Economic Anthropology, gathering contributes far more to the diets of contemporary gathering-hunting societies than hunting does. Rather than staying at the home base, women and children go out gathering in groups several times a week, largely meeting their own nutritional needs as well as sharing with others. Pregnancy and nursing do not significantly limit the subsistence activities of women, as they remain active throughout pregnancy and carry infants in slings or on their hips until the children are able to keep up. While meat is highly valued, it does not make women dependent on men, and the ability to hunt does not make men dominant over women. In most contemporary gathering-hunting societies, men and women are fairly equal.

In archaeology, some feminist researchers have countered the “man the hunter” hypothesis with a “woman the gatherer” hypothesis. These researchers point to fossil evidence suggesting that women’s activities were equally important to survival and development in humans’ evolutionary past. These archaeologists note that the teeth of early hominids indicate that they were omnivorous, eating a wide variety of foods. The very large, well-worn molars of early hominid skulls indicate an adaptation to a diet of gritty foods such as nuts, seeds, and fruits with tough peels. Given the centrality of plant foods to the diets of contemporary gathering-hunting peoples, it seems likely that gathering was also the primary means of food-getting for humans’ ancestors (though, of course, one must be cautious in making such generalizations). If gathering was so crucial, then quite possibly the ingenuity of early hominids might have been focused not only on making hunting gear but also on developing tools for gathering, such as digging sticks and stones for breaking open hard shells. As hominid babies lacked the grasping toes of other apes, it would have been more difficult for them to grasp hold of their mothers as they were carried out on gathering expeditions. Perhaps, then, an important invention might have been a baby sling made of animal skins, an object known as a kaross among the San peoples of the Kalahari in southern Africa. Unfortunately, as digging sticks and baby slings would have been made of organic materials, the fossil record contains no trace of them. While the stone tools used in hunting are prevalent in the fossil record, the organic tools used in gathering would have decomposed long ago.

If gathering was the crucial food-getting strategy of hominins or was at least equal in importance to hunting, then women likely enjoyed considerable social power alongside men. If women were gathering, they probably contributed to the development of the tools associated with gathering. On the move throughout the local environment, women likely knew where to find high-quality foods and when such foods were in season. If women could provide for themselves, they would have been free to become involved in romantic and sexual relationships on their own terms and to leave such relationships when they wanted. What is known about gathering in gathering-hunting societies completely overturns assumptions of male dominance embedded in the “man the hunter” hypothesis.

Beyond “man the hunter” and “woman the gatherer” hypotheses, cultural anthropologists who study gathering-hunting groups point out that the gendered division of labor in gathering-hunting societies is more flexible than these essentialist theories might suggest. In such societies, men also gather plant foods, and women sometimes hunt for honey or kill small game such as lizards and insects. As mentioned in the introduction to this textbook, a team of archaeologists led by Randy Haas recently discovered the 9,000-year-old bones of a woman buried with projectile points and other hunting implements in the Andes of South America (Gibbons 2020). Having reexamined archaeological reports on the burials of 10 other women buried with hunting tools, Haas and his team believe they may also have been female hunters.

As with evidence from primates and human biology, the archaeological evidence for the origins of human gender roles and sexual relations is not definitive. Rather, the main lesson seems to be that humans are biologically flexible and culturally variable in their expressions of gender and sexuality.

This page titled 12.2: Sex, Gender, and Sexuality in Anthropology is shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Jennifer Hasty, David G. Lewis, Marjorie M. Snipes, & Marjorie M. Snipes (OpenStax) via source content that was edited to the style and standards of the LibreTexts platform.