When the ACA was enacted in 2010, Medicaid expansion was a cornerstone of lawmakers’ efforts to expand realistic access to healthcare to as many people as possible. The idea was that everyone with household incomes up to 133% of the federal poverty level (138% with the 5% income disregard) would be able to enroll in Medicaid starting in 2014.

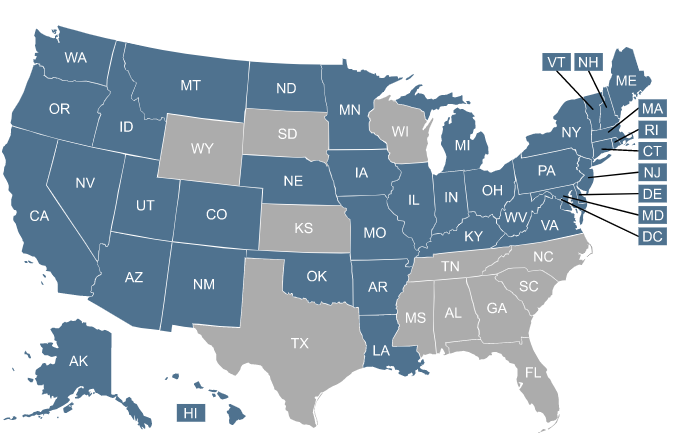

But the Supreme Court later ruled that the expansion of Medicaid eligibility would be optional for states (meaning they wouldn’t lose their federal Medicaid funding if they didn’t expand eligibility), and 10 states still have not expanded Medicaid eligibility as of 2024.

The American Rescue Plan, enacted in March 2021, provides these holdout states with two years of additional federal funding, if they choose to expand Medicaid. Oklahoma, Missouri, South Dakota, and North Carolina have taken advantage of this additional funding.

Since 2010, the number of states that have accepted ACA’s Medicaid expansion has steadily grown – from about half the states in 2014, to 40 states and DC as of 2024.

Georgia implemented a partial expansion of Medicaid in mid-2023, but the program has a work requirement and very few people have enrolled. Georgia’s approach does not count as Medicaid expansion under the ACA, and like Wisconsin (which also has a partial Medicaid expansion program), Georgia is not receiving the enhanced federal funding – or the American Rescue Plan bonus funding – that’s available to states that expand Medicaid. CMS has maintained a clear policy, under the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations, of only providing enhanced federal funding if a state fully expands Medicaid.

There are a host of other Medicaid-related developments in the works across the country – both in expansion and non-expansion states – that could affect eligibility for and access to Medicaid benefits. Some states favor changes that would put increased limits on Medicaid eligibility – such as work requirements and lifetime caps – while other states have considered or implemented legislation to expand access to coverage or give currently ineligible residents a chance to buy into the Medicaid program.

You can select a state on the map below to see specific details about that state’s Medicaid program, how to apply, the status of Medicaid expansion and the effects of Medicaid disenrollment.

| Expansion states |

| States refusing |

Helping millions of Americans since 1999.

Federal legislation to address the COVID pandemic was enacted in March 2020. It gave states additional federal Medicaid funding, but on the condition that they not disenroll anyone from Medicaid during the pandemic. (The specifics of this are addressed in more detail below.) This was originally slated to continue through the end of the COVID public health emergency (which ended on May 11, 2023), but the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, which was enacted in late 2022, provided a specific date — March 31, 2023 — for the end of the Medicaid disenrollment ban. So starting April 1, 2023, states were able to begin disenrolling people who are no longer eligible for Medicaid, as well as people who failed to complete their renewal paperwork. We’ve discussed this in much greater detail in this article, and are providing state-by-state details in our state-specific Medicaid overviews. (Click on a state on the map above for more information.)

The high-level overview is that states began the process of returning to normal eligibility redeterminations in either February, March, or April 2023, and then have 12 months to initiate renewals for their entire Medicaid population, and 14 months to complete the process. (This window has since been extended in many states.) 1 This is referred to as an “unwinding” period. States were allowed to prioritize renewals for people whose coverage had been continued without eligibility redetermination for the longest, or for people who were most likely to no longer be eligible, or they could simply conduct renewals on their regularly scheduled date, without a focus on populations likely to be disenrolled. Regardless of the approach that a state takes, they have to provide publicly available data and monthly updates to the federal government.

There is a lot of variation from one state to another in terms of how this is being handled. And some states have had to pause procedural/administrative disenrollments due to errors that were causing entire families to be disenrolled even when some family members qualified for automatic renewal. But by May 2024, nearly 22 million people had been disenrolled from Medicaid nationwide during the unwinding period. 2

There is an extended special enrollment period on HealthCare.gov, through November 30, 2024, for people who lose Medicaid during the unwinding of the pandemic-era continuous coverage requirement.

Requiring Medicaid enrollees to be working (or volunteering, in school, in job training, etc.) for at least a certain number of hours per week is an idea that tends to be popular with Republican lawmakers. Most people who receive Medicaid benefits are either already working or would be exempt from work requirements (due to being disabled, taking care of a minor child, pregnant, etc.), but the myth of the “welfare queen” (or king) persists, and Medicaid work requirements are seen by some as a solution to a perceived problem.

The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has to approve a Medicaid work requirement before a state can implement it. The Obama administration did not allow any work requirements for Medicaid, but the Trump administration was much more open to the idea.

As of 2020, 12 states had received federal approval for work requirements, and several others had pending waivers or were expected to submit waivers in the near future. But work requirements were only in effect in Utah and Michigan at the start of 2020, and both were soon suspended (Utah’s as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, and Michigan’s as a result of a court order). The Biden administration clearly communicated that it does not consider Medicaid work requirements to be in line with the mission of the Medicaid program, and revoked approval for all of the work requirement waivers that had been approved under the prior administration. (Details below.)

As noted above, Georgia did implement a work requirement in mid-2023, along with a partial expansion of Medicaid. (CMS did not approve the work requirement, but Georgia sued and a judge granted the state the right to implement the work requirement.) Georgia is currently the only state in the country with a Medicaid work requirement. It’s only applicable to adults with income under the federal poverty level who aren’t eligible for Medicaid under any of the traditional eligibility categories. But other states — and federal lawmakers — are once again considering them.

Wisconsin had been working towards implementation of a work requirement in early 2020, which would have been the first work requirement in a state that hasn’t expanded Medicaid. But amid the COVID pandemic, Wisconsin suspended the implementation of the work requirement.

A federal judge overturned federally approved Medicaid work requirements in Arkansas, Kentucky, New Hampshire, and Michigan, citing the fact that numerous people would lose coverage under the work requirements, and the government had done nothing to ameliorate that problem. The Trump administration and some of the affected states appealed the court ruling, and the Supreme Court had planned to hear the case. But the Biden administration clarified that it would not support an appeal of the court rulings that overturned the work requirements, and the Supreme Court pulled the case from its list of scheduled arguments in 2021. In April 2022, the Supreme Court officially threw out the pending cases regarding Medicaid work requirements, noting that the Biden administration’s opposition to Medicaid work requirements makes the cases moot.

In the rest of the states where Medicaid work requirements had been approved, they have either been overturned by a judge, paused or suspended by state administrators, or revoked by the Biden administration.

The work requirement in Arkansas was halted in 2019, New Hampshire had already delayed its program before it was overturned, and Kentucky’s new governor officially withdrew the work requirement proposal soon after taking office. Governors in Virginia and Maine paused or withdrew the Medicaid work requirements in those states.

Notably, the bipartisan Medicaid expansion legislation that was considered (but not enacted) in Kansas in 2020 did not include a work requirement. It called for a work referral program instead, which would have been less costly for the state to administer and would not have resulted in people losing their coverage.

Lawmakers in the states that haven’t expanded Medicaid have continued to introduce legislation each year in an effort to expand coverage.

In 2018, Virginia lawmakers passed a budget that includes Medicaid expansion, with coverage that took effect in January 2019. As of May 2024, more than 668,000 people were enrolled in Virginia Medicaid under the expanded eligibility guidelines. 3

From 2019 through 2022, no additional states enacted legislation to expand Medicaid. But that dry spell ended in 2023 when North Carolina enacted H.76, which called for Medicaid expansion in the state, contingent on the passage of the state’s budget bill. The budget was eventually settled in the fall, and Medicaid expansion began in North Carolina in December 2023. By May 2024, more than 450,000 people had enrolled in expanded Medicaid in North Carolina. 4

Georgia enacted legislation (SB106) in 2019 that allowed the state to submit a Medicaid expansion proposal to CMS, but only for people earning up to 100% of the poverty level (as opposed to 138%, as called for in the ACA). CMS approved the partial expansion to take effect in mid-2021, but rejected the state’s request for full Medicaid expansion funding. After the Biden administration revoked approval for Georgia’s planned work requirement, the state paused implementation of the partial Medicaid expansion. It did eventually take effect in July 2023, but enrollment has remained quite low, due to the work requirement and reporting requirements that go along with it.

In Maine, Utah, Idaho, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Missouri, and South Dakota, Medicaid expansion came about as a result of ballot measures passed by voters.

Medicaid expansion ballot initiatives have passed in 100% of the states that have had them on the ballot (Montana voters did not approve a 2018 measure that would have provided ongoing funding for the state’s Medicaid expansion — which was already in effect — but this did not affect the state’s Medicaid expansion, which continues to be available to eligible residents).

But in most of the remaining non-expansion states, ballot measures to expand Medicaid are not an option. Medicaid expansion advocates in Mississippi had been working to gather signatures for a 2022 ballot measure, but suspended their campaign after a Mississippi Supreme Court decision that currently makes it impossible for a signature-gathering campaign to be successful in the state.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) essentially prevented states from making their eligibility standards any more strict during the COVID public health emergency period than they were as of the start of 2020. As noted above, the end date for this was eventually set as March 31, 2023, decoupling it from the public health emergency (which ended on May 11, 2023).

Section 6008 of the FFCRA provided states with a 6.2 percentage point increase in their federal Medicaid matching funding for the duration of the COVID public health emergency period, as long as the state Medicaid program:

Those rules ended on March 31, 2023, under the terms of the Consolidated Appropriations Act that was enacted in late 2022. Here’s our overview of where things stand at the one-year mark in the “unwinding” of the pandemic-era Medicaid continuous coverage rule..

The following is a summary of what’s happened in each of the states where work requirements had been approved or are pending federal approval:

Work requirements that were in effect in early 2020 but have since been suspended/withdrawn:

Medicaid expansion states where new governors withdrew pending work requirements:

Expansion states where work requirements were approved by HHS under the Trump administration but never took effect (and have since been withdrawn):

Medicaid expansion states with pending work requirement proposals (unlikely to be approved by the Biden administration):

Lawmakers in Louisiana considered several work requirement bills in 2018, but none were enacted. Lawmakers in Pennsylvania passed Medicaid work requirement legislation in 2017 and again in 2018, but Governor Tom Wolf vetoed both bills.

Lawmakers in Alaska considered Medicaid work requirement legislation in 2019, but the measure did not advance to a vote.

Several states that have not expanded Medicaid have sought federal permission to impose Medicaid work requirements, despite the fact that their Medicaid populations are comprised almost entirely of those who are disabled, elderly, or pregnant, as well as children.

The Trump Administration has begun granting work requirements in some of these states, although CMS Administrator, Seema Verma clarified in May 2018 that these states would have to clearly demonstrate how they plan to avoid situations in which people lose access to Medicaid as a result of the work requirement, and yet also do not have access to premium subsidies in the exchange.

Non-expansion states with approved work requirement waivers (largely withdrawn by the Biden administration)

Three non-expansion states were granted federal approval to implement Medicaid work requirements for their existing Medicaid populations, or for a newly-eligible population:

Non-expansion states seeking federal permission to impose a Medicaid work requirement:

Note that these states’ waiver proposals were all pending when the Biden administration took office, and none have been approved. The Biden administration has noted that work requirements are not in line with the overall mission of Medicaid (ensuring access to health care).

Kansas had also requested CMS approval for a work requirement of 20 or 30 hours per week, depending on circumstances. But that provision was later removed from the state’s Medicaid renewal proposal, and the waiver approval that was granted by CMS in December 2018 did not include a work requirement. And the bipartisan Medicaid expansion legislation that Kansas lawmakers considered in 2020 called for a work referral program instead of a work requirement.

Lawmakers in Missouri also considered legislation that called for an 80-hour-per-month work requirement, but the bill did not pass in the 2018 session. And voters in Missouri approved a ballot measure in 2020 that resulted in Medicaid expansion that took effect in late 2021.

Several states have sought CMS approval to implement lifetime caps for Medicaid coverage, including Arizona, Kansas, Maine, Utah, and Wisconsin. But thus far, CMS has not approved this provision for any states. Arizona’s work requirement approval noted that CMS was rejecting the state’s proposal to cap eligibility at five years for people who were subject to, but not in compliance with, the work requirement.

The Trump administration also rejected Arkansas’ proposal to cap Medicaid eligibility at 100% of the poverty level, instead of 138%. The agency also rejected a similar proposal from Utah in 2019, and from Georgia in 2020. Massachusetts submitted a similar request to CMS that was never approved, although Massachusetts has already expanded Medicaid.

And no states have received approval for an asset test for Medicaid. Maine proposed an asset test as part of an 1115 waiver proposal, but that portion of the waiver was not approved.

Several states have received approval, however, to impose premiums on certain Medicaid populations, restrict retroactive eligibility, and require more eligibility redeterminations.

Arkansas pioneered the “private option” approach to the state Medicaid expansion, under which the state uses Medicaid funds to purchase private health insurance in the individual market for Medicaid-eligible enrollees. Some other states followed suit to varying degrees over the coming years, but have since transitioned back to a more traditional approach (Medicaid fee-for-service or Medicaid managed care). Arkansas is the only state that still uses the private option approach, and even Arkansas has temporarily paused the process of automatically enrolling new members in private plans through the exchange.

New Hampshire enacted legislation in 2018 that directed the state to abandon the private approach to Medicaid expansion that was being used in the state at the time (buying policies in the exchange for people eligible for expanded Medicaid) and switch to a Medicaid managed care program instead. The state submitted a waiver amendment proposal to CMS in August 2018, and the transition took effect in 2019.

Iowa’s Medicaid expansion program initially used Medicaid funds to buy marketplace coverage for people with income above the poverty level, but the state switched to regular Medicaid managed care in 2016.

Historically, Medicaid coverage for new mothers only lasted for 60 days after the baby was born. After that, the mother would have to qualify to Medicaid under the parent/caretaker or adult coverage rules, which have lower income limits than those for pregnant women. 5

But in recent years, thanks to additional federal funding, nearly all of the states have extended postpartum Medicaid coverage so that it continues for the mother for 12 months after the baby is born. 6

Under federal rules effective in 2024, all states are required to provide at least 12 months of continuous coverage in Medicaid/CHIP for children under age 19. 7 This means that once a child is determined eligible, their coverage cannot be terminated for at least a year, regardless of changes in circumstances.

(This is in contrast to coverage for adults; unless a state has a waiver from CMS, they must discontinue coverage for an adult who experiences a change in circumstances that makes them no longer eligible, even if it’s been less than a year since their last renewal. 8 )

States can extend the continuous coverage period for children, and some have done so. For example, Oregon, 9 Washington, 10 and New Mexico 11 all provide continuous Medicaid coverage through age six. The means that if a baby or young child is enrolled in Medicaid in those states, their coverage will continue until they turn six, regardless of whether their household continues to meet the eligibility requirements during that time.

Hawaii, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania are all in the process of seeking waivers from CMS that would allow them to provide continuous Medicaid coverage for young children. 8

Some states have also considered the possibility of seeking approval for a Medicaid buy-in program, under which people who aren’t eligible for Medicaid would be allowed to purchase Medicaid coverage.

Nevada lawmakers passed legislation to allow Medicaid buy-in during the 2017 legislative session, but the governor vetoed it. Lawmakers in Colorado, Maryland, and New Mexico considered legislation in 2018 that would direct the state to conduct a study on the feasibility and cost of a Medicaid buy-in program (ie, allowing people who aren’t eligible for Medicaid to purchase Medicaid coverage instead of private market coverage). Colorado lawmakers ultimately did not pass the bill, and neither did Maryland lawmakers. But New Mexico enacted legislation in early 2018 calling for a study on the costs and ramifications of a Medicaid buy-in program. Lawmakers in New Mexico considered SB405 in 2019 (which would have created a Medicaid buy-in program), but it did not pass. Instead, New Mexico opted for a state-run subsidy program that provides additional premium subsidies and cost-sharing subsidies to people with income above the Medicaid eligibility threshold who enroll in private health plans through the exchange.

Minnesota lawmakers considered, but did not pass, a bill in 2017 that would have allowed people to buy into MinnesotaCare, the state’s Basic Health Program (similar to Medicaid, but for people with slightly higher income). This issue has been revisited several times since then, but it hasn’t gone anywhere yet.

Thus far, Medicaid buy-in has not gained much traction. But Democrats have been warming to the idea of a public option or single-payer system. A public option program debuted in 2021 in Washington. Colorado enacted a watered-down version of a public option bill, and the plans became available for 2023 coverage. Nevada enacted public option legislation in 2021 but it won’t take effect until 2026. But none of these states have taken a Medicaid buy-in option.

As noted at the start of this summary, Medicaid was a cornerstone of ACA lawmakers’ efforts to expand access to healthcare. The idea was that everyone with household incomes up to 133% of the federal poverty level (FPL) would be able to enroll in Medicaid (there is a built-in 5% income disregard for MAGI-based Medicaid eligibility, so the threshold ends up being 138% of FPL).

People above that threshold would be eligible for premium tax credits in the exchanges to make their coverage affordable, as long as their income didn’t exceed 400% of the poverty level. The idea was that people with income above 400% of the poverty level would be able to afford coverage without subsidies, but that has not proven to be the case. So the American Rescue Plan temporarily eliminated the income cap for subsidy eligibility, for 2021 and 2022, and the Inflation Reduction Act extended that provision through 2025.

Because Medicaid expansion was expected to be a given in every state, the law was written so that premium subsidies in the exchange are not available to people with incomes below the poverty level. They were supposed to have access to Medicaid instead.

Unfortunately for many low-income individuals, the Supreme Court ruled in 2012 that states could not be penalized for opting out of Medicaid expansion. And 10 states have not yet expanded their programs.

Until late 2015, there were still 22 states that had not expanded Medicaid, but quite a few states have expanded Medicaid since then:

As a result of the holdout states’ refusal to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid, KFF estimates there are about 1.5 million people in the coverage gap across nine of those states (although Wisconsin has not expanded Medicaid under the ACA, BadgerCare Medicaid is available for residents with incomes up to the poverty level, so there is no coverage gap in Wisconsin).

Being in the coverage gap means you have no realistic access to health insurance. These are people with incomes below the poverty level, so they are not eligible for subsidies in the exchange. But they are also not eligible for their state’s Medicaid program.

In many of the states that have not expanded Medicaid, low-income adults without dependent children are ineligible for Medicaid, regardless of how little they earn. For those who do have dependent children, the income limit for eligibility can be very low: In Alabama, parents with dependent children are only eligible for Medicaid if their income doesn’t exceed 18% of the poverty level. 5 For a family of three, that’s only $387 per month in 2024.

New Hampshire, Michigan, Indiana, Pennsylvania, Alaska, Montana, and Louisiana all expanded their Medicaid programs between 2014 and 2016. Expansion took effect in Virginia and Maine in 2019, in Utah, Idaho, and Nebraska in 2020, and in Oklahoma and Missouri in 2021. It took effect in South Dakota and North Carolina in 2023.

The 2018 election was pivotal for Medicaid, with three states passing ballot initiatives to expand Medicaid, and Kansas, Wisconsin, and Maine electing governors who are supportive of Medicaid expansion (Maine voters had already approved Medicaid expansion in the 2017 election, but it wasn’t implemented until early 2019, when the state’s new governor took office).

The first six states to implement Medicaid programs did so in 1966, although several states waited a full four years to do so. And Alaska and Arizona didn’t enact Medicaid until 1972 and 1982, respectively. Eventually, Medicaid was available in every state, but it certainly didn’t happen everywhere in the first year.

There’s big money involved in the Medicaid expansion decision for states. Under ACA rules, the federal government pays the vast majority of the cost of covering people who are newly eligible for Medicaid. Through the end of 2016, the federal government fully funded Medicaid expansion. The states started to pay a small fraction of the cost starting in 2017, eventually paying 10% by 2020. From there, the 90/10 split is permanent; the federal government will always pay 90% of the cost of covering the newly eligible population, assuming the ACA remains in place.

Because the federal government funds nearly all of the cost of Medicaid expansion, the 10 states that haven’t yet taken action to expand Medicaid have been missing out on significant federal funding — more than $305 billion between 2013 and 2022.

(Indiana, Pennsylvania, Alaska, Montana, Louisiana, Virginia, Maine, Utah, Idaho, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Missouri, South Dakota, and North Carolina have expanded their Medicaid programs since that report was produced in 2014, so they are no longer missing out on federal Medicaid expansion funding.)

Just five states – Florida, Texas, North Carolina, Georgia, and Tennessee – would have received nearly 60% of that funding (a total of $227.5 billion) if they had expanded Medicaid to cover their poorest residents starting in 2013. The good news is that although the federal government is no longer funding the full cost to expand Medicaid, they’ll always pay at least 90% of the cost, making the state Medicaid expansion a good deal for states regardless of when they implement it (in other words, for every dollar a state spends to cover its Medicaid expansion population, the federal government will kick in $9).

For residents of states that haven’t expanded Medicaid, their federal tax dollars are being used to pay for Medicaid expansion in other states, while none of the Medicaid expansion funds are coming back to their own states. Between 2013 and 2022, $152 billion in federal taxes was collected from residents in states not expanding Medicaid, and used to fund Medicaid expansion in other states.

Public support for Medicaid expansion is relatively strong, even in Conservative-leaning states: In Wyoming (considered the most Conservative state), 56% of the public support Medicaid expansion. But the Republican-led legislature in Wyoming has consistently rejected Medicaid expansion, despite Republican former Governor Matt Mead’s support for expansion.

Voters in Utah, Idaho, and Nebraska — all conservative-leaning states — approved Medicaid expansion ballot initiatives in the 2018 election. And the same thing happened in Missouri and Oklahoma in 2020, and in South Dakota in 2022.

In Texas – home to more than a quarter of those in the coverage gap nationwide – a board of 15 medical professionals appointed by then-Governor Rick Perry recommended in November 2014 that the state accept federal funding to expand Medicaid, noting that the uninsured rate in Texas was “unacceptable.” But no real progress towards Medicaid expansion has been made since then, and U.S. census data indicated that 16.6% of Texas residents were uninsured in 2022 – by far the highest rate in the country. 12

There are several other states where the legislature or the governor – or both – are generally opposed to the ACA, but where Medicaid expansion has been actively considered, either by the governor or legislature or in negotiations with the federal government. These include Kansas and Tennessee as well as North Carolina, which enacted Medicaid expansion legislation in 2023 after years of political wrangling on the issue.

There’s plenty of activity to monitor at the state level. You can click on a state on this list to see current Medicaid-related legislation: